HOW PAPUA NEW GUINEA IS ADAPTING

TO CLIMATE CHANGE

Mitigating the effects of climate change while adapting to it is at the

heart of PNG’s strategy

Even though Papua New Guinea (PNG) represents less than 1% of the earth’s land mass, it is one of the 10 countries most vulnerable to climate change. This is dire news for these islands that are home to more than 5% of the world’s biodiversity.

PNG is being hammered by extreme climate events and rising seas, while coping with growing food insecurity, changing patterns of disease and growing population pressure on land and resources. Globally, PNG has emerged as a torch-bearer for action against climate change. Nationally, PNG has maintained a strong strategic focus on mitigating the effects of climate while adapting to them. UNDP has been supporting these efforts in four vital areas —

Policy and Legislation

Helping develop better policies, plans and laws on climate change

Mitigation, Including REDD+

Reducing emissions from forest degradation, enhancing forest stocks, and forest management

Communication and Advocacy

Spreading the word about climate change issues and solutions

Research, Plans, Actions

Planning for national adaptation while building community resilience and adaptive capacity

Mitigation and adaptation call for more effective management of Protected Areas (PAs), better forest policies and reporting, disaster preparedness and supported internal migration. Projects are still in progress but some results are already visible and many lessons are being learnt. This case study documents all of them.

Climate change is a juggernaut. It is a faceless monster with no domain. Everything else will become an academic exercise if we do not act now.

Hon. Wera Mori, Former Minister for Environment,

Conservation and Climate Change

THE THREAT

FOUR REASONS WHY CLIMATE CHANGE IS HITTING PNG SO HARD

Heavy weather, growing impacts

In a country where cyclones and floods are growing in intensity and frequency, about 87% of rural Papua New Guineans still depend on rain-fed fresh water to sustain their agriculture and fisheries. This increases their vulnerability to extreme weather events, sea-level rise, salt water intrusion into freshwater resources such as wells, and changing sea currents.

Rising seas, failing crops

Since 1993, sea levels around PNG have been rising by 7 mm per year, more than twice the global average, flooding low-lying coastal areas and lowlands with saltwater. With their crops failing and natural resources depleted, coastal people are fleeing to higher ground, but they pay a heavy price. Field missions have noted lack of drinking water, decreased food security, malnutrition and poor health in many communities. During a visit to the remote Carteret Islands atoll, the Hon. Wera Mori, Former Minister for Environment, Conservation and Climate Change, remarked, “Every night the mothers quietly shed tears on their pillows as they ponder how they will feed their husbands and children. The crops fail because of the rise of saltwater.”

Food insecurity and disease

As crops fail and clean water supplies dwindle, food insecurity, malnutrition and health issues are rising across Papua New Guinea, disproportionately affecting women and children. In a country that is already shouldering a heavy disease burden, spatial patterns of diseases are changing. For example, the incidence of malaria has been steadily rising over the last decade in the Highlands, a region where it was practically unknown before warming temperatures allowed the disease to spread to higher altitudes.

Local threats, biodiversity at risk

PNG’s unique ecosystems, including forests, mangroves and seagrass, are coming under increasing threat as climate change amplifies local issues stemming from land use change, growing human pressure on resources, unregulated anthropogenic fire regimes and others. For example, catches of native fish are declining as tilapia invade the waters. Fishing is nearly impossible now in Lake Lavu because of invasive water lilies.

Climate change hazards in Papua New Guinea at a glance

- El Niño and La Niña events will continue to occur in the future, but there is a little consensus on whether these events will change in intesity or frequency.

- Tropical cyclones are projected to be less frequent but more intense.

- Annual mean temperatures and extremely high daily temeratures will continue to rise.

- Average rainfall is projected to increase in most areas, along with more extreme rain events.

- Droughts are projected to decline in frequency.

- Sea level will continue to rise.

- Ocean acidification is expected to continue.

- The risk of coral bleaching is expected to increase.

- No changes in waves along the Coral Sea coast are projected, while on the northern coasts, December-March wave heights and periods are projected to dec

THE IMPACT

HOW CLIMATE CHANGE WILL AFFECT PNG’S BIODIVERSITY AND NRM

Much of PNG is protected by its natural landscapes. Mangroves help buffer the impacts of storm surges on coastal communities and high levels of forest cover help stabilise the weather and prevent soil loss and flash floods. But in the years ahead, the impacts of climate will threaten the country’s biodiversity and natural resources in unprecedented ways.

3.6°C rise in temperature

by 2090

Biodiversity impact

- PNG’s montane forests are likely to shrink further

- Bird species sensitive to warming may get isolated and be unable to breed as they move up to cooler altitudes

- Botanical diversity will decline by an average of seven species

- 63% of PNG’s plant species will have smaller geographic ranges

- More severe fires

- Invasive plant species

- Coral bleaching will be more likely

10 cms rise in

sea level

by 2100

Biodiversity impact

- Coastal communities may migrate inland or be wiped out

- Increasing erosion will devour beaches and coastal ecosystems

- Saltwater will invade freshwater systems

- Species that nest on cays and beaches may disappear as they lose their breeding grounds

Increase in

ocean acidity

Biodiversity impact

- Growth of corals, crustaceans and molluscs will slow down

- Fisheries and other marine industries will decline, affecting communities that depend on them

More rainfall with greater variability and more extreme weather events

Biodiversity impact

- Population affected by coastal flooding will double

- Devastating landslides that destroy villages, crops and forests will increase

- Crop diversity will decrease

- Forest fires will increase

At present, we are protected from some of the worst impacts of climate change by our unique

natural capital. Mangroves have helped buffer the impacts of storm surges on coastal

communities. High levels of forest cover help maintain weather patterns and reduce soil loss

and flash flooding. Our country acts as one of the most important global sinks for trapping and

storing greenhouse gases by reducing deforestation and promoting forest conservation.

Hon. James Marape, Prime Minister, 2020

THE RESPONSE

FROM WORDS TO ACTION: HOW PNG IS RESPONDING TO CLIMATE CHANGE

PNG is committed to halving its greenhouse emissions by 2030 and becoming carbon neutral by 2050. After signing on to the Paris Agreement in 2015 and committing itself to achieving 78% renewable energy by 2030, it submitted its intended Nationally Determined Contribution (NDC) to the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC), including targets for REDD+ (reducing forest degradation and deforestation and enhancing forest stocks, and forest management).

The timeline below shows PNG’s affiliations and the rapid pace of its response to the evolving climate change crisis it is facing.

Affiliations:

- COP26 Member

- UN Small Island Developing States Chair

- Coalition of Rainforest Nations

Mitigation and adaptation to climate change require policies and plans that can move PNG towards a green economy based on reversing forest loss and land degradation, and preserving its environmental wealth. PNG’s challenge now is to act on its environmental intentions and commitments while ensuring economic progress and a secure social environment.

However, it has been tough going. Despite its pledges to the UNFCCC, PNG lost over a million hectares of tree cover between 2011 and 2020. Some of the reasons for this include the lack of political will to aggressively reduce logging and increase revegetation; lack of supervision, enforcement and transparency in the timber industry; barriers to adopting renewable energy; and plans for new fossil fuel projects.

UNDP is one of the many agencies, governments, and NGOs that are helping PNG to meet its climate commitments.The second Biennial Update Report (BUR2) lists 26 partner projects, and estimates that more than US$1 billion will be needed over the next decade to achieve the Enhanced NDC targets.

Papua New Guinea is one of the 10

countries most vulnerable to

the impacts of climate change. There is no

greater single issue of national interest facing PNG.

Dr John Poulsen, Project Team Leader, UNDP’s Building Resilience to Climate Change

PNG’s evolving role in greenhouse gas emissions and carbon storage

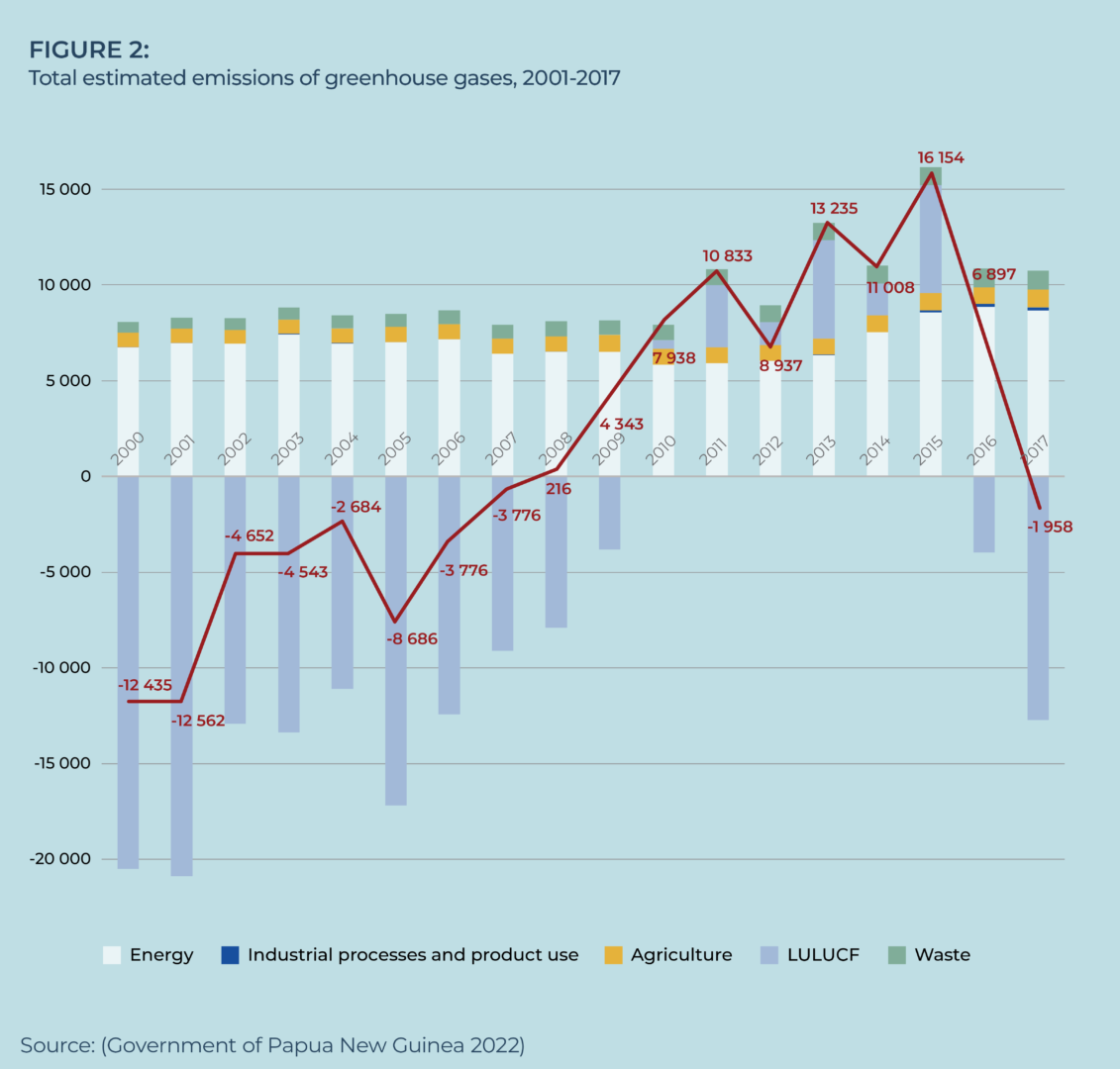

Until 2015, relatively low emissions of greenhouse gases made PNG’s tropical forests a carbon sink, absorbing and storing carbon. About 78% of the country was covered with 12 types of forest that were part of the world’s third-largest contiguous area of forest. However, with accelerating land clearing and land use, over 23% of PNG’s remaining forests had been degraded.

This turned PNG into a net source of carbon until 2017, when net emissions again went below zero thanks to a decline in logging and forest clearing. However, greenhouse gas emissions from energy sources have continued to grow

(Figure 1).

The Enhanced NDC aims to reduce emissions from the land use, land use change and forestry (LULUCF) sector by 10,000 Gg of CO2 per year by 2030 compared to the 2015 level, by reducing deforestation and forest degradation and by revegetation. A recent assessment indicates that these targets are already being exceeded.

UNDP’s role

HELPING PNG MEET ITS CLIMATE CHANGE GOALS

UNDP’s current climate change projects in Papua New Guinea focus on four areas.

Policy development, plans and legislation

Communication

and advocacy

Mitigation

The advancement

of PNG’s National Adaptation Plan Project

1. POLICY DEVELOPMENT, PLANS AND LEGISLATION

As one of the 120 countries participating in UNDP’s Climate Promise program, PNG has received the agency’s support in developing policies and plans for delivering on the climate change goals laid out in its NDC. UNDP also supported the 2022 updating of the NDC to include more than 60 million tonnes reduction of CO2 emissions over the coming decade while delivering economic, social and environmental benefits.

2. COMMUNICATION AND ADVOCACY

UNDP has supported activities that help change hearts and minds about climate change, such as the National Environment and Climate Emergency Summit in 2021. This two-day event, which was live-streamed on social media, helped deepen the commitment of the government, community members and development partners for tackling climate change.

The same year, in preparation for COP26 in Glasgow, UNDP launched a social media campaign to promote a wide range of Papua New Guinean perspectives. The advocacy led to an outcome statement that emphasised the urgent need for more climate-friendly investments, better regulation of sectors that could harm the environment, and greater collaboration between stakeholders.

3. MITIGATION THROUGH REDD+

UNDP has helped PNG to develop REDD+ as an important tool for tackling deforestation, and also supported more sustainable land use planning projects. Two separate projects are helping with the transition to renewable energy —

- Facilitating Renewable Energy and Energy Efficiency Applications for Greenhouse Gas Emission Reduction (FREAGER)

- Support to Rural Entrepreneurship, Investment and Trade (STREIT)

This support will empower PNG to reclaim its status as a sink for greenhouse gases. The revised NDC aims for a reduction of 10,000 Gg of CO2-equivalent and a carbon-neutral energy industries sub-sector by 2030, while the installed capacity of renewable energy is expected to rise from 30% in 2015 to 78% in the same period.

GETTING PNG READY FOR REDD+

Starting in 2015, UNDP has guided PNG towards REDD+ readiness through several phases. A mid-term review of phase one in 2017 noted that PNG had made significant progress towards REDD+ readiness and recommended a project extension with additional funding, though communication, cooperation and insufficient government commitment towards REDD+ continued to be serious concerns.

By the end of phase two, UNDP had successfully brought PNG to REDD+ readiness by strengthening PNG’s capacities related to the National Forest Monitoring System, establishing Forest Reference Emissions Levels and safeguards, and increasing engagement with a range of stakeholders. UNDP worked with the lead implementing agencies — the Office of Climate Change and Development (OCCD) in the first phase and the Climate Change and Development Authority (CCDA) in the second, with the PNG Forest Authority as the lead. FAO, a key implementing partner in REDD+ preparation, helped develop the National Forest Inventory.

The final independent evaluation noted that the project had brought about significant policy reforms by using the National REDD+ Strategy to align land use legislation with policy frameworks for climate change, forestry and land use.

OUTPUTS

- National REDD+ Strategy 2017-2027. Submitted to the UNFCCC in April 2018.

- Forest Reference Emissions Level submitted to the UNFCCC in 2017.

- A National Forest Monitoring System with a web portal.

- National Safeguards Information System. Endorsed by NEC in November 2020.

Our country acts as one of the most important global sinks for trapping and storing greenhouse gases… However, with increasing population and our need for economic development many of these protections are under threat.

Hon. James Marape, Prime Minister, 2020

4. ADVANCING PNG’S NATIONAL ADAPTATION PLAN PROJECT

National Adaptation Plans (NAP), established under the Cancun Adaptation Framework and re-emphasized in the Paris Agreement, seek to identify medium and long-term adaptation needs informed by the latest climate science. At a global level, the NAP process aims to reduce vulnerability and integrate adaptation into new and existing policies. PNG’s National Adaptation Plan (NAP) is the result of a technically robust and inclusive effort led by the PNG government through the CCDA. The NAP’s objectives are to strengthen institutional capacities in priority sectors, build resilience and capacity at all levels, set up early warning systems, and promote investment in priority sectors of climate change adaptation.

Led by the UNDP and CCDA, and working with other development partners, the NAP project will review regulatory and policy frameworks and mainstream CCA into national and sectoral policies and planning documents. Strategic actions will be defined in cross-cutting and sectoral areas to guide PNG in achieving its climate adaptation targets by 2030 through a gender-responsive and whole-of-society approach.

OTHER UNDP-LED CLIMATE INITIATIVES

Bringing power to the people

FACILITATING RENEWABLE ENERGY AND ENERGY EFFICIENCY APPLICATIONS FOR GREENHOUSE GAS EMISSION REDUCTION (FREAGER)

- Less than 15% of PNG’s population has access to electricity, and few settlements away from urban areas are connected to the power grid.

- In rural areas, access to electricity is estimated to be under 3.7%.

- In remote places, generating electricity requires unreliable diesel generators that are expensive to maintain and contribute to poor air quality and increased greenhouse gas emissions.

- Only about 6% of the country uses renewable energy.

FREAGER complements the national electrification plan by helping national agencies to develop the policy and regulatory frameworks for operating off-grid markets using hydro and solar mini-grid systems. By showcasing relevant technologies, the project hopes to achieve the widespread replication of micro- and mini-hydro mini-grids, solar photovoltaic mini-grids, and township energy efficiency programs. At the same time, it aims to remove barriers to these technologies in the areas of policy and planning, technical and commercial viability, financing, and information and awareness. Still in development is a website for telling FREAGER’s story and archiving e-versions of materials produced, with links to articles, legislations, and initiatives.

The FREAGER project has four components:

- Energy policy, planning and Institutional development

- Renewable energy and energy efficiency technology applications

- Project financing

- Awareness raising

Some example projects within these components are described below.

Places in the sun

SUPPORT TO RURAL ENTREPRENEUSHIP, INVESTMENT AND TRADE (STREIT)

Solar panels, backed by the STREIT programme, funded by the EU and joint UN agencies, are coming up in six remote schools and health facilities in the provinces of East Sepik and Sandaun. STREIT’s goal is to increase the use of solar energy to enhance agricultural value chains and improve production, particularly for women-led micro and small enterprises.

Within the project, UNDP’s role is to build capacity and raise public environmental awareness to make the management and maintenance of solar panels more sustainable, including advocacy for the whole-hearted support of district and provincial governments. The project is working with vocational training institutions to develop certified courses in solar installation and maintenance.

Good oceans, great business

Putting the health of the reef first can be a surprisingly good model for so-called ‘blue business’. In PNG’s local language, tok ples, this is expressed as Gutpla solwara, gutpla bisnis (Good oceans, good business). UNDP is in the early stages of a joint project with the UN Capital Development Fund to demonstrate this model’s viability by supporting local blue enterprises, leveraging local skills and ultimately unlocking private capital from domestic and international sources. The project will start with Kimbe Bay (West New Britain) and Milne Bay (Louisiade Archipelago), both sites high in biodiversity and coral reefs. Supported businesses and projects will include marine ecotourism, coral reef restoration and sustainable aquaculture or seaweed farms, among others.

Changing to meet changing times

Building Resilience to Climate Change (BRCC)

Building Resilience to Climate Change in PNG (BRCC) is a five-year program funded by the Asian Development Bank (ADB) through the Pilot Program for Climate Resilience. In PNG, BRCC supports vulnerable islands and atoll communities in the provinces of East New Britain, Manus, Morobe and Milne Bay, and the Autonomous Region of Bougainville.

UNDP’s involvement began in 2020 when it entered a tripartite agreement with ADB and the CCDA to implement and deliver two of BRCC’s components —

Climate change vulnerability assessments and small sub-projects at island level

Many island communities in the five focus areas are vulnerable to sea-level rise, with limited and decreasing freshwater access, food gardens threatened by salt water, and eroding and receding coastlines. Some are isolated and hard to reach, with limited ability to communicate with the outside world. To better understand the needs of these communities, UNDP and its partners developed a bottom-up, community-driven process aligned with local and provincial development plans. The process yielded a summary of each island community’s vulnerabilities and exposure to climate change and disasters. Participants’ priorities on adapting to climate change formed the basis for small-grant sub-project investment proposals.

Food security and fisheries in Manus, East New Britain and Milne Bay

How does climate change affect home food gardens and marine catches? To enhance food security, UNDP is working to identify vulnerabilities of food sources to climate change. Activities include setting up pilot home gardens and locally managed marine areas that can help maintain the health of marine ecosystems, sustain fishing resources and improve watershed integrity.

Outputs

Climate change vulnerability assessments for each island/atoll community.

These will serve as a basis for —

- Investment plans

- Gender-sensitive disaster response strategies and emergency response plans for each community

- Sub-project proposals for enhancing adaptation to climate change. Over 80 have been developed.

- Mainstreaming of climate change vulnerability assessments and sub-project proposals into local and provincial policies and planning

OUTCOMES

BETTER THAN YESTERDAY, EVEN BETTER TOWORROW

The PNG government’s commitment to tackling climate change is stronger today than it has ever been. It has a strong framework for climate change action, with CCA plans headed for endorsement, and its technical reporting capacity is well developed. In recent years, PNG has reclaimed its status as a carbon sink. Thanks to interventions, including some by the UNDP, PNG logged a verifiable decline in the rate of forest clearing from its highs of 2013-2015. The resulting 9 MT carbon emissions reduction will become the first nationally issued REDD+ forestry carbon credits to go on sale to corporations and consumers.

Once it is endorsed and becomes official, PNG’s NAP will spur the phased introduction of CCA into all government activities, beginning in 2023. Phase one will focus on the agriculture, health, infrastructure and transport sectors. The renewed capacity and emerging results will help mitigate some of the dire hardships being faced by Papua New Guineans, especially in low-lying coastal and island communities that are being battered by flooding and rising sea-levels.

LESSONS

These lessons have been developed based on interviews with UNDP project staff, beneficiaries, partners, and government involved in UNDP climate-related projects.

How the past can guide the future.

Robust and meaningful stakeholder consultations are important. A well-structured and deep consultative process with a range of stakeholders can create engagement and ownership across a spectrum of stakeholders and enrich environmental planning and decision-making.

Capacity building and development should be interdisciplinary.

It enables sector specialists to understand mitigation and adaptation targets, and climate specialists to understand sector-specific targets and areas where change is possible. This helps build consensus.

Domestic policy provides a good basis for which to build the NAP.

By grounding early work in existing domestic policies, the NAP process gained rapid buy-in from key government agencies while building existing capacity and understanding of policy options and linkages such as the National REDD+ Strategy and the Forestry Reference Level.

CONCLUSION

THE TIME TO ACT IS NOW

PNG’s Prime Minister James Marape named UNDP as the country’s partner of choice in helping PNG address its climate change issues. As the leading agency among PNG’s development partners, UNDP is ideally placed to play a useful coordinating and facilitative role to minimise overlaps and conflicts and ensure that the country gets the most out of funding opportunities and new technologies.

Through its consultations for the NAP, UNDP brought together a mosaic of stakeholders from different sectors to share their experiences, practices and climate priorities. This greatly helped raise both their awareness and ownership of plans.

Working holistically with policy, advocacy, mitigation and adaptation is crucial for PNG to play its role in carbon storage while protecting its population and biodiversity from the worst effects of climate change.

The time for trials and pilot programs will soon be over. There is a strong policy framework, stated government commitment and a high level of community support for climate change actions. Practitioners have a good idea about what needs to be done. Hard-won gains can be consolidated if more donors and development partners can extend long-term support to worthy institutions and activities. The time to act is already here.